Edited by Gerko Egert, Ilona Hongisto, Michael Hornblow,

Katve-Kaisa Kontturi, Mayra Morales, Ronald Rose-Antoinette,

Adam Szymanski

Editing of the Infrathin by Ramona Benveniste, Csenge Kolozsvari, Mayra Morales & Leslie Plumb

Art Direction, Web Design by Leslie Plumb

NODE:

Ramona Benveniste, Érik Bordeleau, Michael Hornblow, Erin Manning, Brian Massumi, Mayra Morales, Csenge Kolozsvari, Leslie Plumb, Ronald Rose-Antoinette and Adam Szymanski

i - v

Andrew Goodman

1-10

Bodil Marie Stavning Thomsen

11- 19

Pia Ednie-Brown

20 - 48

Jorrit Groot, Toni Pape & Chrys Vilvang

49 - 58

Brian Massumi

59 - 88

Louise Boisclair

89 - 94

Jondi Keane

95 - 109

Mayra Morales

110-115

Ronald Rose-Antoinette

116 - 129

Érik Bordeleau

130 - 153

Melora Koepke

154 - 161

Geoffrey Edwards

162 - 184

Nikki Rotas

185 - 189

Adam Szymanski

190 - 201

Erin Manning

202 - 210

Laura T. Ilea

211 - 221

Michael Hornblow

222 - 238

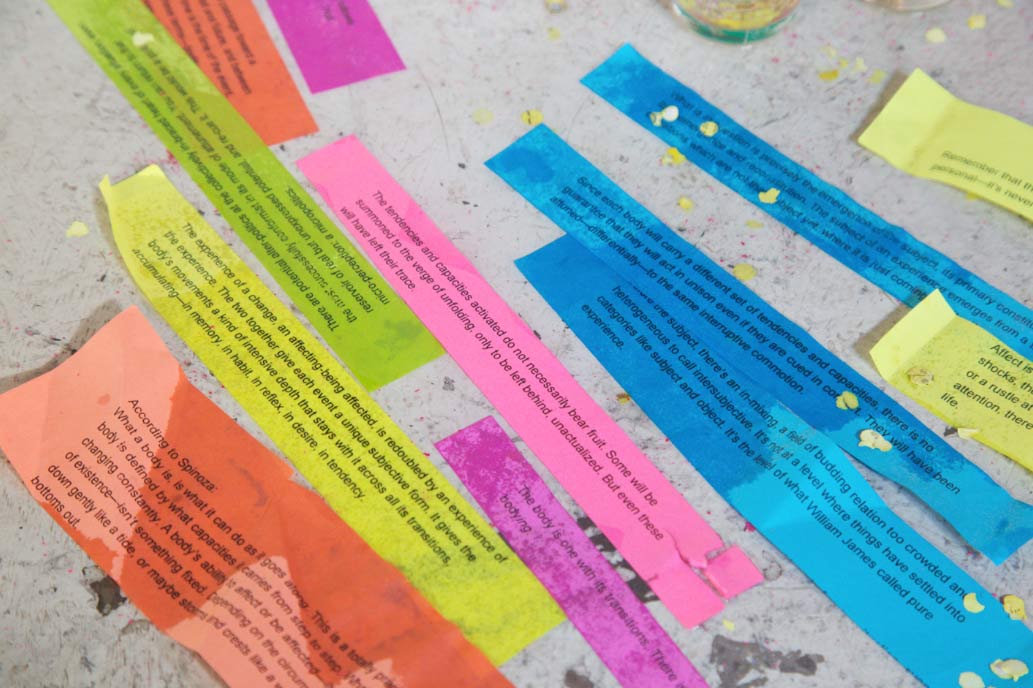

*All images and text woven between the Node articles, unless otherwise noted, are drawn from with 'Movements of Thought' and 'Knots of Thought' workshops, facilitated by Ramona Benveniste, Diego Gil, Csenge Kolozsvari, Mayra Morales & Leslie Plumb, from August 2014 - December 2014. Paper-cut topographies and videos are by Leslie Plumb

TANGENTS

Gerko Egert & Peter Pál Pelbart

239-249

Justy Phillips

250-256

3.

Katja Čičigoj, Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher & Martina Ruhsam

257-273

Samantha Spurr

274-278

Kenneth Bailey & Lori Lobenstine (Design Studio for Social Intervention)

279-284

Hubert Gendron-Blais

285-292

Anique Vered & Joel Mason

293-321

8.

Sissel Marie Tonn

322-325

Elliott Rajnovic

326-332

10.

Karolina Kucia

333-335

Mi-Jeong Lee

336-348

12. Movements of Thought: Ramona Benviniste, Diego Gil, Csenge Kolozsvari, Mayra Morales & Leslie Plumb

attending to the appetitions activat[ing] now, here,

NODE No. 7 - A n i ma ting Bio philo s o p h y

edited by P hill ip T hurtle and A.J. N o c e k

Introduction: Vitalizing Th o u g h t

Phillip Thurtle and A.J. No c e k

i-xi

On Ascensionism

Eugene Thacker

1-7

Biomedia and the Pragmatics of Life in Architectural Design

A.J. Nocek

8-61

Concepts have a life on their own: Biophilosophy, History and Structure in Georges Canguilhem

Henning Schmidgen

62-97

Animation and Vitality

Phillip Thurtle

98-117

dowhile (2009)

Elizabeth Buschmann

Currents (2008)

Stephanie Maxwell

Animation and the Medium of Life

Deborah Levitt

118-161

Finding Animals with Plant Intelligence

Richard Doyle

162-183

TANGENT No. 7

edited by Marie-Pier Boucher and Adam Szymanski

RV (Room Vehicle) Prototype: Where the Surface Meets the Machine

Greg Lynn

184-186

The Rhythmic Dance of (Micro-)Contrasts

Gerko Egert

187-191

Continuous Horizons

Lisa Sommerhuber

192-193

Christian Marclay's The Clock as Relational Environment

Toni Pape

194-207

Rotating Tongues

Elisabeth Brauner

208

In the Middle of it All: Words on and

with Peter Mettler

Adam Szymanski

209-216

Spacestation

Julia Koerner

217

Animal Enrichment and The VivoArts School for Transgenics Aesthetics Ltd.

Adam Zaretsky

218-245

Space Collective

Nora Graw

246

Xanadu_1

Andy Gracie

247-253

To Embrace Golden Beauty: An Interview from Around the Canopy

David Zink-Yi and

Antonio Fernandini-Guerrero

254-265

Into the Midst (*Flash only)

edited by Erin Manning

web design by Leslie Plumb

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

edited by Jondi Keane & Trish Glazebrook

web design by Leslie Plumb

Here Where it Lives...Biocleave

Jondi Keane and Trish Glazebrook

Open Letters

Madeline Gins i-viii

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

Mapping Reversible Destiny

Trish Glazebrook and Sarah Conrad 22-40

Escaping the Museum

David Kolb41-71

Ing

Jean-Jacques Lecercle72-79

The Reversible Eschatology of Arakawa and Gins

Russell Hughes80-102

Chaos, Autopoiesis and/or Leonardo da Vinci/Arakawa

Hideo Kawamoto103–111

Daddy, Why do Things have Outlines?: Constructing the Architectural Body

Helene Frichot112–124

Tentatively Constructing Images: The Dynamism of Piet Mondrian's Paintings

Troy Rhoades125–153

Evidence Architectural Body by Accident, Destiny Reversed by Design

Blair Solovy 154-168

Breathing the Walls

James Cunningham169–188

Technology and the Body Public

Stephen Read189-213

Bioscleave: Shaping our Biological Niches

Stanley Shostak214-224

Arakawa and Gins: The Organism-Person-Environment Process

Eugene Gendlin225-236

An Arakawa and Gins Experimental Teaching Space – A Feasibility Study

Jondi Keane237–252

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

KEYNOTES

The Mechanism of Meaning: A Pedagogical Skecthbook

Gordon Bearn253–269

Wayfinding through Landing Sites and Architectural Bodies: Exploring the Roles of Trajectoriness, Affectivatoriness, and Imaging Along

Reuben Baron 270-285

Trajectory of ARAKAWA Shusaku: from Kan-Oké (Coffin) to the Reversible Destiny Lofts

Fumi Tsukahara286-297

A Snailspace

Tom Conley298–316

Made/line Gins or Arakawa in

Trans-e-lation

Marie Dominique Garnier317–339

The Dance of Attention

Erin Manning340–367

What Counts as Language in a Closely Argued Built-Discourse?

Gregg Lambert 368-380

Constructing Poiesis: Storyboards for an immersive diagramming

Alan Prohm 381–415

Open Wide, Come Inside: Laughter, Composure and Architectural Play

Pia Ednie-Brown416–427

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TRIBUTES

What Arakawa Did

Don Byrd 428–441

Arakawa

Don Ihde 442-445

For Arakawa, Nine More Lives

Jean-Michel Rabaté 446–448

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TANGENTS

Approximately Arakawa and Gins

Ken Wark 448-449

A Perspective of the Universe

Erin Manning and

Brian Massumi

450-458

Axial Lecture on Self-Orientation

George Quasha

Demonstrator

Bob Bowen

Levitation

Bob Bowen

INFLeXions No. 5 - Gilbert Simondon (March 2012)

edited by Marie-Pierre Boucher, Patrick Harrop and Troy Rhoades

Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop i–iii

What is Relational Thinking?

Didier Debaise 1–11

38Hz., 7.5 Minutes

Ted Krueger 12–29

Humans and Machines

Thomas Lamarre 30–68

Simondon, Bioart, and the Milieus of Biotechnology

Rob Mitchell 69–111

Just Noticeable Difference:

Ontogenesis, Performativity and the Perceptual Gap

Chris Salter 112–130

Machine Cinematography

Henning Schmidgen 131–148

Alien Media: Interview with Rafael Lozano–Hemmer

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop 149–160

TANGENTS

Le temps de l’oeuvre, le temps de l’acte: Entretien avec Bernard Aspe

Interview by Erik Bordeleau 161–184

Gobs and Gobs of Metaphor: Larry Bissonette’s Typed Massage

Ralph James Savarese 185–224

Messy Time, Refined

Ronald T Simon

INFLeXions No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience (Nov. 2010)

Transversal Fields of Experience

Christoph Brunner and Troy Rhoades i-viii

ZeNeZ and the Re[a]dShift BOOM!

Sher Doruff 1-32

Body, The Scrivener – The Somagrammical Alphabet Of “Deep”

Kaisa Kurikka and Jukka Sihvonen 33-47

Anarchival Cinemas

Alanna Thain 48-68

Syn-aesthetics – total artwork or difference engine?

Anna Munster 69-94

Icon Icon

Aden Evens 95-117

Edgy Colour: Digital Colour in Experimental Film and Video

Simon Payne 118-140

“Still Life” de Jia Zhangke: Les temps de la rencontre

Erik Bordeleau 141-163

To Dance Life: On Veridiana Zurita’s “Das Partes for Video”

Rick Dolphijn 164-182

Jazz And Emergence (Part One) - From Calculus to Cage, and from Charlie Parker to Ornette Coleman: Complexity and the Aesthetics and Politics of Emergent Form in Jazz

Martin E. Rosenberg 183-277

TANGENTS: No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience

3 Poems

Crina Bondre Ardelean

Healing Series*

Brian Knep 278-280

R.U.N.: A Short Statement on the Work*

Paul Gazzola 281-284

Castings: A Conversation*

Deborah Margo, Bianca Scliar Mancini and Janita Wiersma 285-310

Matter, Manner, Idea

Sjoerd van Tuinen 311-336

On Critique

Brian Massumi 337-340

Loco-Motion* (Flash)

Andrew Murphie 341-343 > HTML version

An Emergent Tuning as Molecular Organizational Mode

Heidi Fast 344-359

Semiotext(e): Interview with Sylvere Lotringer

CoRPosAsSociaDos

Andreia Oliveira

INFLeXions No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

From Noun to Verb: The Micropolitics of "Making Collective" - An Interview between Inflexions Editors Ering Manning & Nasrin Himada

with Erin Manning and Nasrin Himada i-viii

Plants Don't Have Legs - An Interview with Gina Badger

with Gina Badger and Nasrin Himada 1-32

Becoming Apprentice to Materials - An Interview with Adam Bobbette

with Adam Bobbette and Nasrin Himada 33-47

Micropolitics in the Desert - Politics and the Law in Australian Aborigianl Communities" - An Interview with Barbara Glowczewski

with Barbara Glowczewski, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 48-68

Les baleines et la forêt amazonienne - Gabriel Tarde et la cosmopolitique Entrevue avec Bruno Latoure

avec Bruno Latour, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 69-94

Of Whales and the Amazon Forest - Gabriel Tarde and Cosmopolitics Interview with Bruno Latour

with Bruno Latour, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 95-117

Saisir le politique dans l’évènementiel - Entrevue avec Maurizio Lazzarato

avec Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 118-140

Grasping the Political in the Event - Interview with Maurizio Lazzarato

with Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 141-163

Cinematic Practice Does Politics - Interview with Julia Loktev

with Julia Loktev and Nasrin Himada 164-182

Of Microperception and Micropolitics - An Interview with Brian Massumi

with Joel Loktev and Brian Massumi 183-275

Histoire du milieu: entre macro et mésopolique - Entrevue avec Isabelle Stengers

avec Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, et Brian Massumi 183-275

History through the Middle: Between Macro and Mesopolitics - an Interview with Isabelle Stengers

with Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, and Brian Massumi 183-275

Non-NODE non-TANGENT: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Affective Territories by Margarida Carvalho

Margarida Carvalho 183-275

TANGENTS: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Appetite Forever: Amsterdam Molecule*

Rick Dolphi jn and Veridiana Zurita

Digestive Derivatives: Amsterdam Molecule*

Sher Doruff

Body of Water: Weimar Molecule*

João da Silva

Concrete Gardens: Montreal Molecule 1*

Cuerpo Común: Madrid Molecule*

Jaime del Val

Dark Precursor: Naples Molecule*

Beatrice Ferrara, Vito Campanelli, Tiziana Terranova, Michaela Quadraro, Vittorio Milone

Diagramming Movement: London Molecule*

Sebastian Abrahamsson, Gill Clarke, Diana Henry, Jeff Hung, Joe Gerlach, Zeynep Gunduz, Chris Jannides, Thomas Jellis, Derek McCormack, Sarah Rubidge, Alan Stones, Andrew Wilford

Double Booking: Boston Molecule*

www.ds4si.org

Free Phone: San Diego/Tijuana Molecule*

Micha Cardenas, Chris Head, Katherine Sweetman, Camilo Ontiveros, Elle Mehrmand and Felipe Zuniga

Futuring Bodies: Melbourne Molecule*

Tony Yap, Mike Hornblow, Pia Ednie-Brown and her Plastic Futures studio- PALS Plasticity and Autotrophic Life Society, Adele Varcoe and her Fashion Design studio (both from RMIT)

Generative Thought Machine: Sydney Molecule*

Mat Wall-Smith, Anna Munster, Andrew Murphie, Gillian Fuller, Lone Bertelsen

Humboldt's Meal: Berlin Molecule*

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Alex Schweder

Lack of Information: Montreal Molecule 2*

Jonas Fritsch, Christoph Brunner, Joel Mckim, Marie-Eve Bélanger...

Olympic Phi-Fi: London Molecule 2*

M. Beatrice Fazi, Jonathan Fletcher, Caroline Heron, Luciana Parisi

Vagins-à-Dents: Hull Molecule *

Marie-Ève Bélanger, Jean-Pierre Couture, Dalie Giroux, Rebecca Lavoie

Wait: Toronto Molecule*

Alessandra Renzi, Laura Kane

INFLeXions No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus:

the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

Editorial: The Complexity of Collabor(el)ations

Stamatia Portanova

Trilogie Stroboscopique + Lilith

Antonin De Bemels

The Speculative Generalization of the Function: A Key to Whitehead

James Bradley

Propositions for the Verge: William Forsythe's Choreographic Objects

Erin Manning

Extensive Continuum: Towards a Rhythmic Anarchitecture

Steve Goodman & Luciana Parisi

Feeling Feelings: the Work of Russell Dumas through Whitehead's Process and Reality

Philipa Rothfield

Against Full Frontal

Alanna Thain

TANGENT: No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus: the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

edited by Natasha Prévost and Bianca Scliar Mancini (*all tangents require Flash plugins)

Walking Distance from the Studio*

Francis Alÿs

The Red Line

Lex Braes

Research-Creation Collaboration*

Marie Brassard & Alessander MacSween

Occasional Experiences Series (excerpts)*

Gerardo Cibelli

Spatial Vibration: string-based instrumen, study II, 2008*

Olafur Eliasson

Hand's Door*

Michel Groisman

Interview*

Louise Lecavalier

untited*

Otto Oscar Hernández Ruiz

Bending Back In a Field of Experience*

João da Silva

How I learned to stop loving and worry about Dubai*

Charles Stankievech

9MX15*

Vinil Filmes

INFLeXions No. 1- How is Research-Creation?

edited by Alanna Thain, Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Affective Commotion

Alanna Thain

Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion

Erin Manning

The Thinking-Feeling of What Happens: A Semblance of a Conversation

Brian Massumi

Clone your Technics! Research-Creation, Radical Empiricism and the Constraints of Models

Andrew Murphie

Thinking Spaces for Research-Creation

Derek McCormack

Infinity in a Step: On the Compression and Complexity of a Movement Thought

Stamatia Portanova

TANGENTS: No. 1 - How is Research-Creation?

edited by Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Systèmes des Sons

Frédéric Lavoie

What is a Smooth Plane? A journey of Nomadology 001

Yuk Hui

Horizons

Amélie Brisson-Darveau

Fugue Marc Ngui: Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus

Bianca Scliar Mancini

Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus

Marc Ngui

This Was Now; Terrains of Absence

Mark Iwinski

NODE No. 7 - A n i ma ting Bio philo s o p h y

edited by P hill ip T hurtle and A.J. N o c e k

Introduction: Vitalizing Th o u g h t

Phillip Thurtle and A.J. No c e k

i-xi

On Ascensionism

Eugene Thacker

1-7

Biomedia and the Pragmatics of Life in Architectural Design

A.J. Nocek

8-61

Concepts have a life on their own: Biophilosophy, History and Structure in Georges Canguilhem

Henning Schmidgen

62-97

Animation and Vitality

Phillip Thurtle

98-117

dowhile (2009)

Elizabeth Buschmann

Currents (2008)

Stephanie Maxwell

Animation and the Medium of Life

Deborah Levitt

118-161

Finding Animals with Plant Intelligence

Richard Doyle

162-183

TANGENT No. 7

edited by Marie-Pier Boucher and Adam Szymanski

RV (Room Vehicle) Prototype: Where the Surface Meets the Machine

Greg Lynn

184-186

The Rhythmic Dance of (Micro-)Contrasts

Gerko Egert

187-191

Continuous Horizons

Lisa Sommerhuber

192-193

Christian Marclay's The Clock as Relational Environment

Toni Pape

194-207

Rotating Tongues

Elisabeth Brauner

208

In the Middle of it All: Words on and

with Peter Mettler

Adam Szymanski

209-216

Spacestation

Julia Koerner

217

Animal Enrichment and The VivoArts School for Transgenics Aesthetics Ltd.

Adam Zaretsky

218-245

Space Collective

Nora Graw

246

Xanadu_1

Andy Gracie

247-253

To Embrace Golden Beauty: An Interview from Around the Canopy

David Zink-Yi and

Antonio Fernandini-Guerrero

254-265

Into the Midst (*Flash only)

edited by Erin Manning

web design by Leslie Plumb

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

edited by Jondi Keane & Trish Glazebrook

web design by Leslie Plumb

Here Where it Lives...Biocleave

Jondi Keane and Trish Glazebrook

Open Letters

Madeline Gins i-viii

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

Mapping Reversible Destiny

Trish Glazebrook and Sarah Conrad 22-40

Escaping the Museum

David Kolb41-71

Ing

Jean-Jacques Lecercle72-79

The Reversible Eschatology of Arakawa and Gins

Russell Hughes80-102

Chaos, Autopoiesis and/or Leonardo da Vinci/Arakawa

Hideo Kawamoto103–111

Daddy, Why do Things have Outlines?: Constructing the Architectural Body

Helene Frichot112–124

Tentatively Constructing Images: The Dynamism of Piet Mondrian's Paintings

Troy Rhoades125–153

Evidence Architectural Body by Accident, Destiny Reversed by Design

Blair Solovy 154-168

Breathing the Walls

James Cunningham169–188

Technology and the Body Public

Stephen Read189-213

Bioscleave: Shaping our Biological Niches

Stanley Shostak214-224

Arakawa and Gins: The Organism-Person-Environment Process

Eugene Gendlin225-236

An Arakawa and Gins Experimental Teaching Space – A Feasibility Study

Jondi Keane237–252

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

KEYNOTES

The Mechanism of Meaning: A Pedagogical Skecthbook

Gordon Bearn253–269

Wayfinding through Landing Sites and Architectural Bodies: Exploring the Roles of Trajectoriness, Affectivatoriness, and Imaging Along

Reuben Baron 270-285

Trajectory of ARAKAWA Shusaku: from Kan-Oké (Coffin) to the Reversible Destiny Lofts

Fumi Tsukahara286-297

A Snailspace

Tom Conley298–316

Made/line Gins or Arakawa in

Trans-e-lation

Marie Dominique Garnier317–339

The Dance of Attention

Erin Manning340–367

What Counts as Language in a Closely Argued Built-Discourse?

Gregg Lambert 368-380

Constructing Poiesis: Storyboards for an immersive diagramming

Alan Prohm 381–415

Open Wide, Come Inside: Laughter, Composure and Architectural Play

Pia Ednie-Brown416–427

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TRIBUTES

What Arakawa Did

Don Byrd 428–441

Arakawa

Don Ihde 442-445

For Arakawa, Nine More Lives

Jean-Michel Rabaté 446–448

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TANGENTS

Approximately Arakawa and Gins

Ken Wark 448-449

A Perspective of the Universe

Erin Manning and

Brian Massumi

450-458

Axial Lecture on Self-Orientation

George Quasha

Demonstrator

Bob Bowen

Levitation

Bob Bowen

INFLeXions No. 5 - Gilbert Simondon (March 2012)

edited by Marie-Pierre Boucher, Patrick Harrop and Troy Rhoades

Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop i–iii

What is Relational Thinking?

Didier Debaise 1–11

38Hz., 7.5 Minutes

Ted Krueger 12–29

Humans and Machines

Thomas Lamarre 30–68

Simondon, Bioart, and the Milieus of Biotechnology

Rob Mitchell 69–111

Just Noticeable Difference:

Ontogenesis, Performativity and the Perceptual Gap

Chris Salter 112–130

Machine Cinematography

Henning Schmidgen 131–148

Alien Media: Interview with Rafael Lozano–Hemmer

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop 149–160

TANGENTS

Le temps de l’oeuvre, le temps de l’acte: Entretien avec Bernard Aspe

Interview by Erik Bordeleau 161–184

Gobs and Gobs of Metaphor: Larry Bissonette’s Typed Massage

Ralph James Savarese 185–224

Messy Time, Refined

Ronald T Simon

INFLeXions No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience (Nov. 2010)

Transversal Fields of Experience

Christoph Brunner and Troy Rhoades i-viii

ZeNeZ and the Re[a]dShift BOOM!

Sher Doruff 1-32

Body, The Scrivener – The Somagrammical Alphabet Of “Deep”

Kaisa Kurikka and Jukka Sihvonen 33-47

Anarchival Cinemas

Alanna Thain 48-68

Syn-aesthetics – total artwork or difference engine?

Anna Munster 69-94

Icon Icon

Aden Evens 95-117

Edgy Colour: Digital Colour in Experimental Film and Video

Simon Payne 118-140

“Still Life” de Jia Zhangke: Les temps de la rencontre

Erik Bordeleau 141-163

To Dance Life: On Veridiana Zurita’s “Das Partes for Video”

Rick Dolphijn 164-182

Jazz And Emergence (Part One) - From Calculus to Cage, and from Charlie Parker to Ornette Coleman: Complexity and the Aesthetics and Politics of Emergent Form in Jazz

Martin E. Rosenberg 183-277

TANGENTS: No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience

3 Poems

Crina Bondre Ardelean

Healing Series*

Brian Knep 278-280

R.U.N.: A Short Statement on the Work*

Paul Gazzola 281-284

Castings: A Conversation*

Deborah Margo, Bianca Scliar Mancini and Janita Wiersma 285-310

Matter, Manner, Idea

Sjoerd van Tuinen 311-336

On Critique

Brian Massumi 337-340

Loco-Motion* (Flash)

Andrew Murphie 341-343 > HTML version

An Emergent Tuning as Molecular Organizational Mode

Heidi Fast 344-359

Semiotext(e): Interview with Sylvere Lotringer

CoRPosAsSociaDos

Andreia Oliveira

INFLeXions No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

From Noun to Verb: The Micropolitics of "Making Collective" - An Interview between Inflexions Editors Ering Manning & Nasrin Himada

with Erin Manning and Nasrin Himada i-viii

Plants Don't Have Legs - An Interview with Gina Badger

with Gina Badger and Nasrin Himada 1-32

Becoming Apprentice to Materials - An Interview with Adam Bobbette

with Adam Bobbette and Nasrin Himada 33-47

Micropolitics in the Desert - Politics and the Law in Australian Aborigianl Communities" - An Interview with Barbara Glowczewski

with Barbara Glowczewski, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 48-68

Les baleines et la forêt amazonienne - Gabriel Tarde et la cosmopolitique Entrevue avec Bruno Latoure

avec Bruno Latour, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 69-94

Of Whales and the Amazon Forest - Gabriel Tarde and Cosmopolitics Interview with Bruno Latour

with Bruno Latour, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 95-117

Saisir le politique dans l’évènementiel - Entrevue avec Maurizio Lazzarato

avec Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 118-140

Grasping the Political in the Event - Interview with Maurizio Lazzarato

with Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 141-163

Cinematic Practice Does Politics - Interview with Julia Loktev

with Julia Loktev and Nasrin Himada 164-182

Of Microperception and Micropolitics - An Interview with Brian Massumi

with Joel Loktev and Brian Massumi 183-275

Histoire du milieu: entre macro et mésopolique - Entrevue avec Isabelle Stengers

avec Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, et Brian Massumi 183-275

History through the Middle: Between Macro and Mesopolitics - an Interview with Isabelle Stengers

with Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, and Brian Massumi 183-275

Non-NODE non-TANGENT: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Affective Territories by Margarida Carvalho

Margarida Carvalho 183-275

TANGENTS: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Appetite Forever: Amsterdam Molecule*

Rick Dolphi jn and Veridiana Zurita

Digestive Derivatives: Amsterdam Molecule*

Sher Doruff

Body of Water: Weimar Molecule*

João da Silva

Concrete Gardens: Montreal Molecule 1*

Cuerpo Común: Madrid Molecule*

Jaime del Val

Dark Precursor: Naples Molecule*

Beatrice Ferrara, Vito Campanelli, Tiziana Terranova, Michaela Quadraro, Vittorio Milone

Diagramming Movement: London Molecule*

Sebastian Abrahamsson, Gill Clarke, Diana Henry, Jeff Hung, Joe Gerlach, Zeynep Gunduz, Chris Jannides, Thomas Jellis, Derek McCormack, Sarah Rubidge, Alan Stones, Andrew Wilford

Double Booking: Boston Molecule*

www.ds4si.org

Free Phone: San Diego/Tijuana Molecule*

Micha Cardenas, Chris Head, Katherine Sweetman, Camilo Ontiveros, Elle Mehrmand and Felipe Zuniga

Futuring Bodies: Melbourne Molecule*

Tony Yap, Mike Hornblow, Pia Ednie-Brown and her Plastic Futures studio- PALS Plasticity and Autotrophic Life Society, Adele Varcoe and her Fashion Design studio (both from RMIT)

Generative Thought Machine: Sydney Molecule*

Mat Wall-Smith, Anna Munster, Andrew Murphie, Gillian Fuller, Lone Bertelsen

Humboldt's Meal: Berlin Molecule*

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Alex Schweder

Lack of Information: Montreal Molecule 2*

Jonas Fritsch, Christoph Brunner, Joel Mckim, Marie-Eve Bélanger...

Olympic Phi-Fi: London Molecule 2*

M. Beatrice Fazi, Jonathan Fletcher, Caroline Heron, Luciana Parisi

Vagins-à-Dents: Hull Molecule *

Marie-Ève Bélanger, Jean-Pierre Couture, Dalie Giroux, Rebecca Lavoie

Wait: Toronto Molecule*

Alessandra Renzi, Laura Kane

INFLeXions No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus:

the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

Editorial: The Complexity of Collabor(el)ations

Stamatia Portanova

Trilogie Stroboscopique + Lilith

Antonin De Bemels

The Speculative Generalization of the Function: A Key to Whitehead

James Bradley

Propositions for the Verge: William Forsythe's Choreographic Objects

Erin Manning

Extensive Continuum: Towards a Rhythmic Anarchitecture

Steve Goodman & Luciana Parisi

Feeling Feelings: the Work of Russell Dumas through Whitehead's Process and Reality

Philipa Rothfield

Against Full Frontal

Alanna Thain

TANGENT: No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus: the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

edited by Natasha Prévost and Bianca Scliar Mancini (*all tangents require Flash plugins)

Walking Distance from the Studio*

Francis Alÿs

The Red Line

Lex Braes

Research-Creation Collaboration*

Marie Brassard & Alessander MacSween

Occasional Experiences Series (excerpts)*

Gerardo Cibelli

Spatial Vibration: string-based instrumen, study II, 2008*

Olafur Eliasson

Hand's Door*

Michel Groisman

Interview*

Louise Lecavalier

untited*

Otto Oscar Hernández Ruiz

Bending Back In a Field of Experience*

João da Silva

How I learned to stop loving and worry about Dubai*

Charles Stankievech

9MX15*

Vinil Filmes

INFLeXions No. 1- How is Research-Creation?

edited by Alanna Thain, Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Affective Commotion

Alanna Thain

Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion

Erin Manning

The Thinking-Feeling of What Happens: A Semblance of a Conversation

Brian Massumi

Clone your Technics! Research-Creation, Radical Empiricism and the Constraints of Models

Andrew Murphie

Thinking Spaces for Research-Creation

Derek McCormack

Infinity in a Step: On the Compression and Complexity of a Movement Thought

Stamatia Portanova

TANGENTS: No. 1 - How is Research-Creation?

edited by Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Systèmes des Sons

Frédéric Lavoie

What is a Smooth Plane? A journey of Nomadology 001

Yuk Hui

Horizons

Amélie Brisson-Darveau

Fugue Marc Ngui: Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus

Bianca Scliar Mancini

Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus

Marc Ngui

This Was Now; Terrains of Absence

Mark Iwinski

NODE No. 7 - A n i ma ting Bio philo s o p h y

edited by P hill ip T hurtle and A.J. N o c e k

Introduction: Vitalizing Th o u g h t

Phillip Thurtle and A.J. No c e k

i-xi

On Ascensionism

Eugene Thacker

1-7

Biomedia and the Pragmatics of Life in Architectural Design

A.J. Nocek

8-61

Concepts have a life on their own: Biophilosophy, History and Structure in Georges Canguilhem

Henning Schmidgen

62-97

Animation and Vitality

Phillip Thurtle

98-117

dowhile (2009)

Elizabeth Buschmann

Currents (2008)

Stephanie Maxwell

Animation and the Medium of Life

Deborah Levitt

118-161

Finding Animals with Plant Intelligence

Richard Doyle

162-183

TANGENT No. 7

edited by Marie-Pier Boucher and Adam Szymanski

RV (Room Vehicle) Prototype: Where the Surface Meets the Machine

Greg Lynn

184-186

The Rhythmic Dance of (Micro-)Contrasts

Gerko Egert

187-191

Continuous Horizons

Lisa Sommerhuber

192-193

Christian Marclay's The Clock as Relational Environment

Toni Pape

194-207

Rotating Tongues

Elisabeth Brauner

208

In the Middle of it All: Words on and

with Peter Mettler

Adam Szymanski

209-216

Spacestation

Julia Koerner

217

Animal Enrichment and The VivoArts School for Transgenics Aesthetics Ltd.

Adam Zaretsky

218-245

Space Collective

Nora Graw

246

Xanadu_1

Andy Gracie

247-253

To Embrace Golden Beauty: An Interview from Around the Canopy

David Zink-Yi and

Antonio Fernandini-Guerrero

254-265

Into the Midst (*Flash only)

edited by Erin Manning

web design by Leslie Plumb

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

edited by Jondi Keane & Trish Glazebrook

web design by Leslie Plumb

Here Where it Lives...Biocleave

Jondi Keane and Trish Glazebrook

Open Letters

Madeline Gins i-viii

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

Mapping Reversible Destiny

Trish Glazebrook and Sarah Conrad 22-40

Escaping the Museum

David Kolb41-71

Ing

Jean-Jacques Lecercle72-79

The Reversible Eschatology of Arakawa and Gins

Russell Hughes80-102

Chaos, Autopoiesis and/or Leonardo da Vinci/Arakawa

Hideo Kawamoto103–111

Daddy, Why do Things have Outlines?: Constructing the Architectural Body

Helene Frichot112–124

Tentatively Constructing Images: The Dynamism of Piet Mondrian's Paintings

Troy Rhoades125–153

Evidence Architectural Body by Accident, Destiny Reversed by Design

Blair Solovy 154-168

Breathing the Walls

James Cunningham169–188

Technology and the Body Public

Stephen Read189-213

Bioscleave: Shaping our Biological Niches

Stanley Shostak214-224

Arakawa and Gins: The Organism-Person-Environment Process

Eugene Gendlin225-236

An Arakawa and Gins Experimental Teaching Space – A Feasibility Study

Jondi Keane237–252

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

KEYNOTES

The Mechanism of Meaning: A Pedagogical Skecthbook

Gordon Bearn253–269

Wayfinding through Landing Sites and Architectural Bodies: Exploring the Roles of Trajectoriness, Affectivatoriness, and Imaging Along

Reuben Baron 270-285

Trajectory of ARAKAWA Shusaku: from Kan-Oké (Coffin) to the Reversible Destiny Lofts

Fumi Tsukahara286-297

A Snailspace

Tom Conley298–316

Made/line Gins or Arakawa in

Trans-e-lation

Marie Dominique Garnier317–339

The Dance of Attention

Erin Manning340–367

What Counts as Language in a Closely Argued Built-Discourse?

Gregg Lambert 368-380

Constructing Poiesis: Storyboards for an immersive diagramming

Alan Prohm 381–415

Open Wide, Come Inside: Laughter, Composure and Architectural Play

Pia Ednie-Brown416–427

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TRIBUTES

What Arakawa Did

Don Byrd 428–441

Arakawa

Don Ihde 442-445

For Arakawa, Nine More Lives

Jean-Michel Rabaté 446–448

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TANGENTS

Approximately Arakawa and Gins

Ken Wark 448-449

A Perspective of the Universe

Erin Manning and

Brian Massumi

450-458

Axial Lecture on Self-Orientation

George Quasha

Demonstrator

Bob Bowen

Levitation

Bob Bowen

INFLeXions No. 5 - Gilbert Simondon (March 2012)

edited by Marie-Pierre Boucher, Patrick Harrop and Troy Rhoades

Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop i–iii

What is Relational Thinking?

Didier Debaise 1–11

38Hz., 7.5 Minutes

Ted Krueger 12–29

Humans and Machines

Thomas Lamarre 30–68

Simondon, Bioart, and the Milieus of Biotechnology

Rob Mitchell 69–111

Just Noticeable Difference:

Ontogenesis, Performativity and the Perceptual Gap

Chris Salter 112–130

Machine Cinematography

Henning Schmidgen 131–148

Alien Media: Interview with Rafael Lozano–Hemmer

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop 149–160

TANGENTS

Le temps de l’oeuvre, le temps de l’acte: Entretien avec Bernard Aspe

Interview by Erik Bordeleau 161–184

Gobs and Gobs of Metaphor: Larry Bissonette’s Typed Massage

Ralph James Savarese 185–224

Messy Time, Refined

Ronald T Simon

INFLeXions No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience (Nov. 2010)

Transversal Fields of Experience

Christoph Brunner and Troy Rhoades i-viii

ZeNeZ and the Re[a]dShift BOOM!

Sher Doruff 1-32

Body, The Scrivener – The Somagrammical Alphabet Of “Deep”

Kaisa Kurikka and Jukka Sihvonen 33-47

Anarchival Cinemas

Alanna Thain 48-68

Syn-aesthetics – total artwork or difference engine?

Anna Munster 69-94

Icon Icon

Aden Evens 95-117

Edgy Colour: Digital Colour in Experimental Film and Video

Simon Payne 118-140

“Still Life” de Jia Zhangke: Les temps de la rencontre

Erik Bordeleau 141-163

To Dance Life: On Veridiana Zurita’s “Das Partes for Video”

Rick Dolphijn 164-182

Jazz And Emergence (Part One) - From Calculus to Cage, and from Charlie Parker to Ornette Coleman: Complexity and the Aesthetics and Politics of Emergent Form in Jazz

Martin E. Rosenberg 183-277

TANGENTS: No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience

3 Poems

Crina Bondre Ardelean

Healing Series*

Brian Knep 278-280

R.U.N.: A Short Statement on the Work*

Paul Gazzola 281-284

Castings: A Conversation*

Deborah Margo, Bianca Scliar Mancini and Janita Wiersma 285-310

Matter, Manner, Idea

Sjoerd van Tuinen 311-336

On Critique

Brian Massumi 337-340

Loco-Motion* (Flash)

Andrew Murphie 341-343 > HTML version

An Emergent Tuning as Molecular Organizational Mode

Heidi Fast 344-359

Semiotext(e): Interview with Sylvere Lotringer

CoRPosAsSociaDos

Andreia Oliveira

INFLeXions No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

From Noun to Verb: The Micropolitics of "Making Collective" - An Interview between Inflexions Editors Ering Manning & Nasrin Himada

with Erin Manning and Nasrin Himada i-viii

Plants Don't Have Legs - An Interview with Gina Badger

with Gina Badger and Nasrin Himada 1-32

Becoming Apprentice to Materials - An Interview with Adam Bobbette

with Adam Bobbette and Nasrin Himada 33-47

Micropolitics in the Desert - Politics and the Law in Australian Aborigianl Communities" - An Interview with Barbara Glowczewski

with Barbara Glowczewski, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 48-68

Les baleines et la forêt amazonienne - Gabriel Tarde et la cosmopolitique Entrevue avec Bruno Latoure

avec Bruno Latour, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 69-94

Of Whales and the Amazon Forest - Gabriel Tarde and Cosmopolitics Interview with Bruno Latour

with Bruno Latour, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 95-117

Saisir le politique dans l’évènementiel - Entrevue avec Maurizio Lazzarato

avec Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 118-140

Grasping the Political in the Event - Interview with Maurizio Lazzarato

with Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 141-163

Cinematic Practice Does Politics - Interview with Julia Loktev

with Julia Loktev and Nasrin Himada 164-182

Of Microperception and Micropolitics - An Interview with Brian Massumi

with Joel Loktev and Brian Massumi 183-275

Histoire du milieu: entre macro et mésopolique - Entrevue avec Isabelle Stengers

avec Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, et Brian Massumi 183-275

History through the Middle: Between Macro and Mesopolitics - an Interview with Isabelle Stengers

with Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, and Brian Massumi 183-275

Non-NODE non-TANGENT: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Affective Territories by Margarida Carvalho

Margarida Carvalho 183-275

TANGENTS: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Appetite Forever: Amsterdam Molecule*

Rick Dolphi jn and Veridiana Zurita

Digestive Derivatives: Amsterdam Molecule*

Sher Doruff

Body of Water: Weimar Molecule*

João da Silva

Concrete Gardens: Montreal Molecule 1*

Cuerpo Común: Madrid Molecule*

Jaime del Val

Dark Precursor: Naples Molecule*

Beatrice Ferrara, Vito Campanelli, Tiziana Terranova, Michaela Quadraro, Vittorio Milone

Diagramming Movement: London Molecule*

Sebastian Abrahamsson, Gill Clarke, Diana Henry, Jeff Hung, Joe Gerlach, Zeynep Gunduz, Chris Jannides, Thomas Jellis, Derek McCormack, Sarah Rubidge, Alan Stones, Andrew Wilford

Double Booking: Boston Molecule*

www.ds4si.org

Free Phone: San Diego/Tijuana Molecule*

Micha Cardenas, Chris Head, Katherine Sweetman, Camilo Ontiveros, Elle Mehrmand and Felipe Zuniga

Futuring Bodies: Melbourne Molecule*

Tony Yap, Mike Hornblow, Pia Ednie-Brown and her Plastic Futures studio- PALS Plasticity and Autotrophic Life Society, Adele Varcoe and her Fashion Design studio (both from RMIT)

Generative Thought Machine: Sydney Molecule*

Mat Wall-Smith, Anna Munster, Andrew Murphie, Gillian Fuller, Lone Bertelsen

Humboldt's Meal: Berlin Molecule*

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Alex Schweder

Lack of Information: Montreal Molecule 2*

Jonas Fritsch, Christoph Brunner, Joel Mckim, Marie-Eve Bélanger...

Olympic Phi-Fi: London Molecule 2*

M. Beatrice Fazi, Jonathan Fletcher, Caroline Heron, Luciana Parisi

Vagins-à-Dents: Hull Molecule *

Marie-Ève Bélanger, Jean-Pierre Couture, Dalie Giroux, Rebecca Lavoie

Wait: Toronto Molecule*

Alessandra Renzi, Laura Kane

INFLeXions No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus:

the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

Editorial: The Complexity of Collabor(el)ations

Stamatia Portanova

Trilogie Stroboscopique + Lilith

Antonin De Bemels

The Speculative Generalization of the Function: A Key to Whitehead

James Bradley

Propositions for the Verge: William Forsythe's Choreographic Objects

Erin Manning

Extensive Continuum: Towards a Rhythmic Anarchitecture

Steve Goodman & Luciana Parisi

Feeling Feelings: the Work of Russell Dumas through Whitehead's Process and Reality

Philipa Rothfield

Against Full Frontal

Alanna Thain

TANGENT: No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus: the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

edited by Natasha Prévost and Bianca Scliar Mancini (*all tangents require Flash plugins)

Walking Distance from the Studio*

Francis Alÿs

The Red Line

Lex Braes

Research-Creation Collaboration*

Marie Brassard & Alessander MacSween

Occasional Experiences Series (excerpts)*

Gerardo Cibelli

Spatial Vibration: string-based instrumen, study II, 2008*

Olafur Eliasson

Hand's Door*

Michel Groisman

Interview*

Louise Lecavalier

untited*

Otto Oscar Hernández Ruiz

Bending Back In a Field of Experience*

João da Silva

How I learned to stop loving and worry about Dubai*

Charles Stankievech

9MX15*

Vinil Filmes

INFLeXions No. 1- How is Research-Creation?

edited by Alanna Thain, Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Affective Commotion

Alanna Thain

Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion

Erin Manning

The Thinking-Feeling of What Happens: A Semblance of a Conversation

Brian Massumi

Clone your Technics! Research-Creation, Radical Empiricism and the Constraints of Models

Andrew Murphie

Thinking Spaces for Research-Creation

Derek McCormack

Infinity in a Step: On the Compression and Complexity of a Movement Thought

Stamatia Portanova

TANGENTS: No. 1 - How is Research-Creation?

edited by Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Systèmes des Sons

Frédéric Lavoie

What is a Smooth Plane? A journey of Nomadology 001

Yuk Hui

Horizons

Amélie Brisson-Darveau

Fugue Marc Ngui: Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus

Bianca Scliar Mancini

Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus

Marc Ngui

This Was Now; Terrains of Absence

Mark Iwinski

NODE No. 7 - A n i ma ting Bio philo s o p h y

edited by P hill ip T hurtle and A.J. N o c e k

Introduction: Vitalizing Th o u g h t

Phillip Thurtle and A.J. No c e k

i-xi

On Ascensionism

Eugene Thacker

1-7

Biomedia and the Pragmatics of Life in Architectural Design

A.J. Nocek

8-61

Concepts have a life on their own: Biophilosophy, History and Structure in Georges Canguilhem

Henning Schmidgen

62-97

Animation and Vitality

Phillip Thurtle

98-117

dowhile (2009)

Elizabeth Buschmann

Currents (2008)

Stephanie Maxwell

Animation and the Medium of Life

Deborah Levitt

118-161

Finding Animals with Plant Intelligence

Richard Doyle

162-183

TANGENT No. 7

edited by Marie-Pier Boucher and Adam Szymanski

RV (Room Vehicle) Prototype: Where the Surface Meets the Machine

Greg Lynn

184-186

The Rhythmic Dance of (Micro-)Contrasts

Gerko Egert

187-191

Continuous Horizons

Lisa Sommerhuber

192-193

Christian Marclay's The Clock as Relational Environment

Toni Pape

194-207

Rotating Tongues

Elisabeth Brauner

208

In the Middle of it All: Words on and

with Peter Mettler

Adam Szymanski

209-216

Spacestation

Julia Koerner

217

Animal Enrichment and The VivoArts School for Transgenics Aesthetics Ltd.

Adam Zaretsky

218-245

Space Collective

Nora Graw

246

Xanadu_1

Andy Gracie

247-253

To Embrace Golden Beauty: An Interview from Around the Canopy

David Zink-Yi and

Antonio Fernandini-Guerrero

254-265

Into the Midst (*Flash only)

edited by Erin Manning

web design by Leslie Plumb

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

edited by Jondi Keane & Trish Glazebrook

web design by Leslie Plumb

Here Where it Lives...Biocleave

Jondi Keane and Trish Glazebrook

Open Letters

Madeline Gins i-viii

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

Mapping Reversible Destiny

Trish Glazebrook and Sarah Conrad 22-40

Escaping the Museum

David Kolb41-71

Ing

Jean-Jacques Lecercle72-79

The Reversible Eschatology of Arakawa and Gins

Russell Hughes80-102

Chaos, Autopoiesis and/or Leonardo da Vinci/Arakawa

Hideo Kawamoto103–111

Daddy, Why do Things have Outlines?: Constructing the Architectural Body

Helene Frichot112–124

Tentatively Constructing Images: The Dynamism of Piet Mondrian's Paintings

Troy Rhoades125–153

Evidence Architectural Body by Accident, Destiny Reversed by Design

Blair Solovy 154-168

Breathing the Walls

James Cunningham169–188

Technology and the Body Public

Stephen Read189-213

Bioscleave: Shaping our Biological Niches

Stanley Shostak214-224

Arakawa and Gins: The Organism-Person-Environment Process

Eugene Gendlin225-236

An Arakawa and Gins Experimental Teaching Space – A Feasibility Study

Jondi Keane237–252

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

KEYNOTES

The Mechanism of Meaning: A Pedagogical Skecthbook

Gordon Bearn253–269

Wayfinding through Landing Sites and Architectural Bodies: Exploring the Roles of Trajectoriness, Affectivatoriness, and Imaging Along

Reuben Baron 270-285

Trajectory of ARAKAWA Shusaku: from Kan-Oké (Coffin) to the Reversible Destiny Lofts

Fumi Tsukahara286-297

A Snailspace

Tom Conley298–316

Made/line Gins or Arakawa in

Trans-e-lation

Marie Dominique Garnier317–339

The Dance of Attention

Erin Manning340–367

What Counts as Language in a Closely Argued Built-Discourse?

Gregg Lambert 368-380

Constructing Poiesis: Storyboards for an immersive diagramming

Alan Prohm 381–415

Open Wide, Come Inside: Laughter, Composure and Architectural Play

Pia Ednie-Brown416–427

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TRIBUTES

What Arakawa Did

Don Byrd 428–441

Arakawa

Don Ihde 442-445

For Arakawa, Nine More Lives

Jean-Michel Rabaté 446–448

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TANGENTS

Approximately Arakawa and Gins

Ken Wark 448-449

A Perspective of the Universe

Erin Manning and

Brian Massumi

450-458

Axial Lecture on Self-Orientation

George Quasha

Demonstrator

Bob Bowen

Levitation

Bob Bowen

INFLeXions No. 5 - Gilbert Simondon (March 2012)

edited by Marie-Pierre Boucher, Patrick Harrop and Troy Rhoades

Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop i–iii

What is Relational Thinking?

Didier Debaise 1–11

38Hz., 7.5 Minutes

Ted Krueger 12–29

Humans and Machines

Thomas Lamarre 30–68

Simondon, Bioart, and the Milieus of Biotechnology

Rob Mitchell 69–111

Just Noticeable Difference:

Ontogenesis, Performativity and the Perceptual Gap

Chris Salter 112–130

Machine Cinematography

Henning Schmidgen 131–148

Alien Media: Interview with Rafael Lozano–Hemmer

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop 149–160

TANGENTS

Le temps de l’oeuvre, le temps de l’acte: Entretien avec Bernard Aspe

Interview by Erik Bordeleau 161–184

Gobs and Gobs of Metaphor: Larry Bissonette’s Typed Massage

Ralph James Savarese 185–224

Messy Time, Refined

Ronald T Simon

INFLeXions No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience (Nov. 2010)

Transversal Fields of Experience

Christoph Brunner and Troy Rhoades i-viii

ZeNeZ and the Re[a]dShift BOOM!

Sher Doruff 1-32

Body, The Scrivener – The Somagrammical Alphabet Of “Deep”

Kaisa Kurikka and Jukka Sihvonen 33-47

Anarchival Cinemas

Alanna Thain 48-68

Syn-aesthetics – total artwork or difference engine?

Anna Munster 69-94

Icon Icon

Aden Evens 95-117

Edgy Colour: Digital Colour in Experimental Film and Video

Simon Payne 118-140

“Still Life” de Jia Zhangke: Les temps de la rencontre

Erik Bordeleau 141-163

To Dance Life: On Veridiana Zurita’s “Das Partes for Video”

Rick Dolphijn 164-182

Jazz And Emergence (Part One) - From Calculus to Cage, and from Charlie Parker to Ornette Coleman: Complexity and the Aesthetics and Politics of Emergent Form in Jazz

Martin E. Rosenberg 183-277

TANGENTS: No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience

3 Poems

Crina Bondre Ardelean

Healing Series*

Brian Knep 278-280

R.U.N.: A Short Statement on the Work*

Paul Gazzola 281-284

Castings: A Conversation*

Deborah Margo, Bianca Scliar Mancini and Janita Wiersma 285-310

Matter, Manner, Idea

Sjoerd van Tuinen 311-336

On Critique

Brian Massumi 337-340

Loco-Motion* (Flash)

Andrew Murphie 341-343 > HTML version

An Emergent Tuning as Molecular Organizational Mode

Heidi Fast 344-359

Semiotext(e): Interview with Sylvere Lotringer

CoRPosAsSociaDos

Andreia Oliveira

INFLeXions No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

From Noun to Verb: The Micropolitics of "Making Collective" - An Interview between Inflexions Editors Ering Manning & Nasrin Himada

with Erin Manning and Nasrin Himada i-viii

Plants Don't Have Legs - An Interview with Gina Badger

with Gina Badger and Nasrin Himada 1-32

Becoming Apprentice to Materials - An Interview with Adam Bobbette

with Adam Bobbette and Nasrin Himada 33-47

Micropolitics in the Desert - Politics and the Law in Australian Aborigianl Communities" - An Interview with Barbara Glowczewski

with Barbara Glowczewski, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 48-68

Les baleines et la forêt amazonienne - Gabriel Tarde et la cosmopolitique Entrevue avec Bruno Latoure

avec Bruno Latour, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 69-94

Of Whales and the Amazon Forest - Gabriel Tarde and Cosmopolitics Interview with Bruno Latour

with Bruno Latour, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 95-117

Saisir le politique dans l’évènementiel - Entrevue avec Maurizio Lazzarato

avec Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 118-140

Grasping the Political in the Event - Interview with Maurizio Lazzarato

with Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 141-163

Cinematic Practice Does Politics - Interview with Julia Loktev

with Julia Loktev and Nasrin Himada 164-182

Of Microperception and Micropolitics - An Interview with Brian Massumi

with Joel Loktev and Brian Massumi 183-275

Histoire du milieu: entre macro et mésopolique - Entrevue avec Isabelle Stengers

avec Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, et Brian Massumi 183-275

History through the Middle: Between Macro and Mesopolitics - an Interview with Isabelle Stengers

with Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, and Brian Massumi 183-275

Non-NODE non-TANGENT: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Affective Territories by Margarida Carvalho

Margarida Carvalho 183-275

TANGENTS: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Appetite Forever: Amsterdam Molecule*

Rick Dolphi jn and Veridiana Zurita

Digestive Derivatives: Amsterdam Molecule*

Sher Doruff

Body of Water: Weimar Molecule*

João da Silva

Concrete Gardens: Montreal Molecule 1*

Cuerpo Común: Madrid Molecule*

Jaime del Val

Dark Precursor: Naples Molecule*

Beatrice Ferrara, Vito Campanelli, Tiziana Terranova, Michaela Quadraro, Vittorio Milone

Diagramming Movement: London Molecule*

Sebastian Abrahamsson, Gill Clarke, Diana Henry, Jeff Hung, Joe Gerlach, Zeynep Gunduz, Chris Jannides, Thomas Jellis, Derek McCormack, Sarah Rubidge, Alan Stones, Andrew Wilford

Double Booking: Boston Molecule*

www.ds4si.org

Free Phone: San Diego/Tijuana Molecule*

Micha Cardenas, Chris Head, Katherine Sweetman, Camilo Ontiveros, Elle Mehrmand and Felipe Zuniga

Futuring Bodies: Melbourne Molecule*

Tony Yap, Mike Hornblow, Pia Ednie-Brown and her Plastic Futures studio- PALS Plasticity and Autotrophic Life Society, Adele Varcoe and her Fashion Design studio (both from RMIT)

Generative Thought Machine: Sydney Molecule*

Mat Wall-Smith, Anna Munster, Andrew Murphie, Gillian Fuller, Lone Bertelsen

Humboldt's Meal: Berlin Molecule*

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Alex Schweder

Lack of Information: Montreal Molecule 2*

Jonas Fritsch, Christoph Brunner, Joel Mckim, Marie-Eve Bélanger...

Olympic Phi-Fi: London Molecule 2*

M. Beatrice Fazi, Jonathan Fletcher, Caroline Heron, Luciana Parisi

Vagins-à-Dents: Hull Molecule *

Marie-Ève Bélanger, Jean-Pierre Couture, Dalie Giroux, Rebecca Lavoie

Wait: Toronto Molecule*

Alessandra Renzi, Laura Kane

INFLeXions No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus:

the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

Editorial: The Complexity of Collabor(el)ations

Stamatia Portanova

Trilogie Stroboscopique + Lilith

Antonin De Bemels

The Speculative Generalization of the Function: A Key to Whitehead

James Bradley

Propositions for the Verge: William Forsythe's Choreographic Objects

Erin Manning

Extensive Continuum: Towards a Rhythmic Anarchitecture

Steve Goodman & Luciana Parisi

Feeling Feelings: the Work of Russell Dumas through Whitehead's Process and Reality

Philipa Rothfield

Against Full Frontal

Alanna Thain

TANGENT: No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus: the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

edited by Natasha Prévost and Bianca Scliar Mancini (*all tangents require Flash plugins)

Walking Distance from the Studio*

Francis Alÿs

The Red Line

Lex Braes

Research-Creation Collaboration*

Marie Brassard & Alessander MacSween

Occasional Experiences Series (excerpts)*

Gerardo Cibelli

Spatial Vibration: string-based instrumen, study II, 2008*

Olafur Eliasson

Hand's Door*

Michel Groisman

Interview*

Louise Lecavalier

untited*

Otto Oscar Hernández Ruiz

Bending Back In a Field of Experience*

João da Silva

How I learned to stop loving and worry about Dubai*

Charles Stankievech

9MX15*

Vinil Filmes

INFLeXions No. 1- How is Research-Creation?

edited by Alanna Thain, Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Affective Commotion

Alanna Thain

Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion

Erin Manning

The Thinking-Feeling of What Happens: A Semblance of a Conversation

Brian Massumi

Clone your Technics! Research-Creation, Radical Empiricism and the Constraints of Models

Andrew Murphie

Thinking Spaces for Research-Creation

Derek McCormack

Infinity in a Step: On the Compression and Complexity of a Movement Thought

Stamatia Portanova

TANGENTS: No. 1 - How is Research-Creation?

edited by Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Systèmes des Sons

Frédéric Lavoie

What is a Smooth Plane? A journey of Nomadology 001

Yuk Hui

Horizons

Amélie Brisson-Darveau

Fugue Marc Ngui: Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus

Bianca Scliar Mancini

Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus

Marc Ngui

This Was Now; Terrains of Absence

Mark Iwinski

NODE No. 7 - A n i ma ting Bio philo s o p h y

edited by P hill ip T hurtle and A.J. N o c e k

Introduction: Vitalizing Th o u g h t

Phillip Thurtle and A.J. No c e k

i-xi

On Ascensionism

Eugene Thacker

1-7

Biomedia and the Pragmatics of Life in Architectural Design

A.J. Nocek

8-61

Concepts have a life on their own: Biophilosophy, History and Structure in Georges Canguilhem

Henning Schmidgen

62-97

Animation and Vitality

Phillip Thurtle

98-117

dowhile (2009)

Elizabeth Buschmann

Currents (2008)

Stephanie Maxwell

Animation and the Medium of Life

Deborah Levitt

118-161

Finding Animals with Plant Intelligence

Richard Doyle

162-183

TANGENT No. 7

edited by Marie-Pier Boucher and Adam Szymanski

RV (Room Vehicle) Prototype: Where the Surface Meets the Machine

Greg Lynn

184-186

The Rhythmic Dance of (Micro-)Contrasts

Gerko Egert

187-191

Continuous Horizons

Lisa Sommerhuber

192-193

Christian Marclay's The Clock as Relational Environment

Toni Pape

194-207

Rotating Tongues

Elisabeth Brauner

208

In the Middle of it All: Words on and

with Peter Mettler

Adam Szymanski

209-216

Spacestation

Julia Koerner

217

Animal Enrichment and The VivoArts School for Transgenics Aesthetics Ltd.

Adam Zaretsky

218-245

Space Collective

Nora Graw

246

Xanadu_1

Andy Gracie

247-253

To Embrace Golden Beauty: An Interview from Around the Canopy

David Zink-Yi and

Antonio Fernandini-Guerrero

254-265

Into the Midst (*Flash only)

edited by Erin Manning

web design by Leslie Plumb

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

edited by Jondi Keane & Trish Glazebrook

web design by Leslie Plumb

Here Where it Lives...Biocleave

Jondi Keane and Trish Glazebrook

Open Letters

Madeline Gins i-viii

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

Mapping Reversible Destiny

Trish Glazebrook and Sarah Conrad 22-40

Escaping the Museum

David Kolb41-71

Ing

Jean-Jacques Lecercle72-79

The Reversible Eschatology of Arakawa and Gins

Russell Hughes80-102

Chaos, Autopoiesis and/or Leonardo da Vinci/Arakawa

Hideo Kawamoto103–111

Daddy, Why do Things have Outlines?: Constructing the Architectural Body

Helene Frichot112–124

Tentatively Constructing Images: The Dynamism of Piet Mondrian's Paintings

Troy Rhoades125–153

Evidence Architectural Body by Accident, Destiny Reversed by Design

Blair Solovy 154-168

Breathing the Walls

James Cunningham169–188

Technology and the Body Public

Stephen Read189-213

Bioscleave: Shaping our Biological Niches

Stanley Shostak214-224

Arakawa and Gins: The Organism-Person-Environment Process

Eugene Gendlin225-236

An Arakawa and Gins Experimental Teaching Space – A Feasibility Study

Jondi Keane237–252

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

KEYNOTES

The Mechanism of Meaning: A Pedagogical Skecthbook

Gordon Bearn253–269

Wayfinding through Landing Sites and Architectural Bodies: Exploring the Roles of Trajectoriness, Affectivatoriness, and Imaging Along

Reuben Baron 270-285

Trajectory of ARAKAWA Shusaku: from Kan-Oké (Coffin) to the Reversible Destiny Lofts

Fumi Tsukahara286-297

A Snailspace

Tom Conley298–316

Made/line Gins or Arakawa in

Trans-e-lation

Marie Dominique Garnier317–339

The Dance of Attention

Erin Manning340–367

What Counts as Language in a Closely Argued Built-Discourse?

Gregg Lambert 368-380

Constructing Poiesis: Storyboards for an immersive diagramming

Alan Prohm 381–415

Open Wide, Come Inside: Laughter, Composure and Architectural Play

Pia Ednie-Brown416–427

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TRIBUTES

What Arakawa Did

Don Byrd 428–441

Arakawa

Don Ihde 442-445

For Arakawa, Nine More Lives

Jean-Michel Rabaté 446–448

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TANGENTS

Approximately Arakawa and Gins

Ken Wark 448-449

A Perspective of the Universe

Erin Manning and

Brian Massumi

450-458

Axial Lecture on Self-Orientation

George Quasha

Demonstrator

Bob Bowen

Levitation

Bob Bowen

INFLeXions No. 5 - Gilbert Simondon (March 2012)

edited by Marie-Pierre Boucher, Patrick Harrop and Troy Rhoades

Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop i–iii

What is Relational Thinking?

Didier Debaise 1–11

38Hz., 7.5 Minutes

Ted Krueger 12–29

Humans and Machines

Thomas Lamarre 30–68

Simondon, Bioart, and the Milieus of Biotechnology

Rob Mitchell 69–111

Just Noticeable Difference:

Ontogenesis, Performativity and the Perceptual Gap

Chris Salter 112–130

Machine Cinematography

Henning Schmidgen 131–148

Alien Media: Interview with Rafael Lozano–Hemmer

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop 149–160

TANGENTS

Le temps de l’oeuvre, le temps de l’acte: Entretien avec Bernard Aspe

Interview by Erik Bordeleau 161–184

Gobs and Gobs of Metaphor: Larry Bissonette’s Typed Massage

Ralph James Savarese 185–224

Messy Time, Refined

Ronald T Simon

INFLeXions No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience (Nov. 2010)

Transversal Fields of Experience

Christoph Brunner and Troy Rhoades i-viii

ZeNeZ and the Re[a]dShift BOOM!

Sher Doruff 1-32

Body, The Scrivener – The Somagrammical Alphabet Of “Deep”

Kaisa Kurikka and Jukka Sihvonen 33-47

Anarchival Cinemas

Alanna Thain 48-68

Syn-aesthetics – total artwork or difference engine?

Anna Munster 69-94

Icon Icon

Aden Evens 95-117

Edgy Colour: Digital Colour in Experimental Film and Video

Simon Payne 118-140

“Still Life” de Jia Zhangke: Les temps de la rencontre

Erik Bordeleau 141-163

To Dance Life: On Veridiana Zurita’s “Das Partes for Video”

Rick Dolphijn 164-182

Jazz And Emergence (Part One) - From Calculus to Cage, and from Charlie Parker to Ornette Coleman: Complexity and the Aesthetics and Politics of Emergent Form in Jazz

Martin E. Rosenberg 183-277

TANGENTS: No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience

3 Poems

Crina Bondre Ardelean

Healing Series*

Brian Knep 278-280

R.U.N.: A Short Statement on the Work*

Paul Gazzola 281-284

Castings: A Conversation*

Deborah Margo, Bianca Scliar Mancini and Janita Wiersma 285-310

Matter, Manner, Idea

Sjoerd van Tuinen 311-336

On Critique

Brian Massumi 337-340

Loco-Motion* (Flash)

Andrew Murphie 341-343 > HTML version

An Emergent Tuning as Molecular Organizational Mode

Heidi Fast 344-359

Semiotext(e): Interview with Sylvere Lotringer

CoRPosAsSociaDos

Andreia Oliveira

INFLeXions No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

From Noun to Verb: The Micropolitics of "Making Collective" - An Interview between Inflexions Editors Ering Manning & Nasrin Himada

with Erin Manning and Nasrin Himada i-viii

Plants Don't Have Legs - An Interview with Gina Badger

with Gina Badger and Nasrin Himada 1-32

Becoming Apprentice to Materials - An Interview with Adam Bobbette

with Adam Bobbette and Nasrin Himada 33-47

Micropolitics in the Desert - Politics and the Law in Australian Aborigianl Communities" - An Interview with Barbara Glowczewski

with Barbara Glowczewski, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 48-68

Les baleines et la forêt amazonienne - Gabriel Tarde et la cosmopolitique Entrevue avec Bruno Latoure

avec Bruno Latour, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 69-94

Of Whales and the Amazon Forest - Gabriel Tarde and Cosmopolitics Interview with Bruno Latour

with Bruno Latour, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 95-117

Saisir le politique dans l’évènementiel - Entrevue avec Maurizio Lazzarato

avec Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning et Brian Massumi 118-140

Grasping the Political in the Event - Interview with Maurizio Lazzarato

with Maurizio Lazzarato, Erin Manning and Brian Massumi 141-163

Cinematic Practice Does Politics - Interview with Julia Loktev

with Julia Loktev and Nasrin Himada 164-182

Of Microperception and Micropolitics - An Interview with Brian Massumi

with Joel Loktev and Brian Massumi 183-275

Histoire du milieu: entre macro et mésopolique - Entrevue avec Isabelle Stengers

avec Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, et Brian Massumi 183-275

History through the Middle: Between Macro and Mesopolitics - an Interview with Isabelle Stengers

with Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, and Brian Massumi 183-275

Non-NODE non-TANGENT: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Affective Territories by Margarida Carvalho

Margarida Carvalho 183-275

TANGENTS: No. 3 - Micropolitics: Exploring Ethico-Aesthetics

Appetite Forever: Amsterdam Molecule*

Rick Dolphi jn and Veridiana Zurita

Digestive Derivatives: Amsterdam Molecule*

Sher Doruff

Body of Water: Weimar Molecule*

João da Silva

Concrete Gardens: Montreal Molecule 1*

Cuerpo Común: Madrid Molecule*

Jaime del Val

Dark Precursor: Naples Molecule*

Beatrice Ferrara, Vito Campanelli, Tiziana Terranova, Michaela Quadraro, Vittorio Milone

Diagramming Movement: London Molecule*

Sebastian Abrahamsson, Gill Clarke, Diana Henry, Jeff Hung, Joe Gerlach, Zeynep Gunduz, Chris Jannides, Thomas Jellis, Derek McCormack, Sarah Rubidge, Alan Stones, Andrew Wilford

Double Booking: Boston Molecule*

www.ds4si.org

Free Phone: San Diego/Tijuana Molecule*

Micha Cardenas, Chris Head, Katherine Sweetman, Camilo Ontiveros, Elle Mehrmand and Felipe Zuniga

Futuring Bodies: Melbourne Molecule*

Tony Yap, Mike Hornblow, Pia Ednie-Brown and her Plastic Futures studio- PALS Plasticity and Autotrophic Life Society, Adele Varcoe and her Fashion Design studio (both from RMIT)

Generative Thought Machine: Sydney Molecule*

Mat Wall-Smith, Anna Munster, Andrew Murphie, Gillian Fuller, Lone Bertelsen

Humboldt's Meal: Berlin Molecule*

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Alex Schweder

Lack of Information: Montreal Molecule 2*

Jonas Fritsch, Christoph Brunner, Joel Mckim, Marie-Eve Bélanger...

Olympic Phi-Fi: London Molecule 2*

M. Beatrice Fazi, Jonathan Fletcher, Caroline Heron, Luciana Parisi

Vagins-à-Dents: Hull Molecule *

Marie-Ève Bélanger, Jean-Pierre Couture, Dalie Giroux, Rebecca Lavoie

Wait: Toronto Molecule*

Alessandra Renzi, Laura Kane

INFLeXions No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus:

the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

Editorial: The Complexity of Collabor(el)ations

Stamatia Portanova

Trilogie Stroboscopique + Lilith

Antonin De Bemels

The Speculative Generalization of the Function: A Key to Whitehead

James Bradley

Propositions for the Verge: William Forsythe's Choreographic Objects

Erin Manning

Extensive Continuum: Towards a Rhythmic Anarchitecture

Steve Goodman & Luciana Parisi

Feeling Feelings: the Work of Russell Dumas through Whitehead's Process and Reality

Philipa Rothfield

Against Full Frontal

Alanna Thain

TANGENT: No. 2 - Rhythmic Nexus: the Felt Togetherness of Movement and Thought

edited by Natasha Prévost and Bianca Scliar Mancini (*all tangents require Flash plugins)

Walking Distance from the Studio*

Francis Alÿs

The Red Line

Lex Braes

Research-Creation Collaboration*

Marie Brassard & Alessander MacSween

Occasional Experiences Series (excerpts)*

Gerardo Cibelli

Spatial Vibration: string-based instrumen, study II, 2008*

Olafur Eliasson

Hand's Door*

Michel Groisman

Interview*

Louise Lecavalier

untited*

Otto Oscar Hernández Ruiz

Bending Back In a Field of Experience*

João da Silva

How I learned to stop loving and worry about Dubai*

Charles Stankievech

9MX15*

Vinil Filmes

INFLeXions No. 1- How is Research-Creation?

edited by Alanna Thain, Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Affective Commotion

Alanna Thain

Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion

Erin Manning

The Thinking-Feeling of What Happens: A Semblance of a Conversation

Brian Massumi

Clone your Technics! Research-Creation, Radical Empiricism and the Constraints of Models

Andrew Murphie

Thinking Spaces for Research-Creation

Derek McCormack

Infinity in a Step: On the Compression and Complexity of a Movement Thought

Stamatia Portanova

TANGENTS: No. 1 - How is Research-Creation?

edited by Christoph Brunner and Natasha Prevost

Systèmes des Sons

Frédéric Lavoie

What is a Smooth Plane? A journey of Nomadology 001

Yuk Hui

Horizons

Amélie Brisson-Darveau

Fugue Marc Ngui: Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus

Bianca Scliar Mancini

Diagrams for Deleuze & Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus

Marc Ngui

This Was Now; Terrains of Absence

Mark Iwinski

NODE No. 7 - A n i ma ting Bio philo s o p h y

edited by P hill ip T hurtle and A.J. N o c e k

Introduction: Vitalizing Th o u g h t

Phillip Thurtle and A.J. No c e k

i-xi

On Ascensionism

Eugene Thacker

1-7

Biomedia and the Pragmatics of Life in Architectural Design

A.J. Nocek

8-61

Concepts have a life on their own: Biophilosophy, History and Structure in Georges Canguilhem

Henning Schmidgen

62-97

Animation and Vitality

Phillip Thurtle

98-117

dowhile (2009)

Elizabeth Buschmann

Currents (2008)

Stephanie Maxwell

Animation and the Medium of Life

Deborah Levitt

118-161

Finding Animals with Plant Intelligence

Richard Doyle

162-183

TANGENT No. 7

edited by Marie-Pier Boucher and Adam Szymanski

RV (Room Vehicle) Prototype: Where the Surface Meets the Machine

Greg Lynn

184-186

The Rhythmic Dance of (Micro-)Contrasts

Gerko Egert

187-191

Continuous Horizons

Lisa Sommerhuber

192-193

Christian Marclay's The Clock as Relational Environment

Toni Pape

194-207

Rotating Tongues

Elisabeth Brauner

208

In the Middle of it All: Words on and

with Peter Mettler

Adam Szymanski

209-216

Spacestation

Julia Koerner

217

Animal Enrichment and The VivoArts School for Transgenics Aesthetics Ltd.

Adam Zaretsky

218-245

Space Collective

Nora Graw

246

Xanadu_1

Andy Gracie

247-253

To Embrace Golden Beauty: An Interview from Around the Canopy

David Zink-Yi and

Antonio Fernandini-Guerrero

254-265

Into the Midst (*Flash only)

edited by Erin Manning

web design by Leslie Plumb

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

edited by Jondi Keane & Trish Glazebrook

web design by Leslie Plumb

Here Where it Lives...Biocleave

Jondi Keane and Trish Glazebrook

Open Letters

Madeline Gins i-viii

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

Mapping Reversible Destiny

Trish Glazebrook and Sarah Conrad 22-40

Escaping the Museum

David Kolb41-71

Ing

Jean-Jacques Lecercle72-79

The Reversible Eschatology of Arakawa and Gins

Russell Hughes80-102

Chaos, Autopoiesis and/or Leonardo da Vinci/Arakawa

Hideo Kawamoto103–111

Daddy, Why do Things have Outlines?: Constructing the Architectural Body

Helene Frichot112–124

Tentatively Constructing Images: The Dynamism of Piet Mondrian's Paintings

Troy Rhoades125–153

Evidence Architectural Body by Accident, Destiny Reversed by Design

Blair Solovy 154-168

Breathing the Walls

James Cunningham169–188

Technology and the Body Public

Stephen Read189-213

Bioscleave: Shaping our Biological Niches

Stanley Shostak214-224

Arakawa and Gins: The Organism-Person-Environment Process

Eugene Gendlin225-236

An Arakawa and Gins Experimental Teaching Space – A Feasibility Study

Jondi Keane237–252

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

KEYNOTES

The Mechanism of Meaning: A Pedagogical Skecthbook

Gordon Bearn253–269

Wayfinding through Landing Sites and Architectural Bodies: Exploring the Roles of Trajectoriness, Affectivatoriness, and Imaging Along

Reuben Baron 270-285

Trajectory of ARAKAWA Shusaku: from Kan-Oké (Coffin) to the Reversible Destiny Lofts

Fumi Tsukahara286-297

A Snailspace

Tom Conley298–316

Made/line Gins or Arakawa in

Trans-e-lation

Marie Dominique Garnier317–339

The Dance of Attention

Erin Manning340–367

What Counts as Language in a Closely Argued Built-Discourse?

Gregg Lambert 368-380

Constructing Poiesis: Storyboards for an immersive diagramming

Alan Prohm 381–415

Open Wide, Come Inside: Laughter, Composure and Architectural Play

Pia Ednie-Brown416–427

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TRIBUTES

What Arakawa Did

Don Byrd 428–441

Arakawa

Don Ihde 442-445

For Arakawa, Nine More Lives

Jean-Michel Rabaté 446–448

No. 6 Arakawa & Gins, a special issue of Inflexions

TANGENTS

Approximately Arakawa and Gins

Ken Wark 448-449

A Perspective of the Universe

Erin Manning and

Brian Massumi

450-458

Axial Lecture on Self-Orientation

George Quasha

Demonstrator

Bob Bowen

Levitation

Bob Bowen

INFLeXions No. 5 - Gilbert Simondon (March 2012)

edited by Marie-Pierre Boucher, Patrick Harrop and Troy Rhoades

Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop i–iii

What is Relational Thinking?

Didier Debaise 1–11

38Hz., 7.5 Minutes

Ted Krueger 12–29

Humans and Machines

Thomas Lamarre 30–68

Simondon, Bioart, and the Milieus of Biotechnology

Rob Mitchell 69–111

Just Noticeable Difference:

Ontogenesis, Performativity and the Perceptual Gap

Chris Salter 112–130

Machine Cinematography

Henning Schmidgen 131–148

Alien Media: Interview with Rafael Lozano–Hemmer

Marie–Pier Boucher and Patrick Harrop 149–160

TANGENTS

Le temps de l’oeuvre, le temps de l’acte: Entretien avec Bernard Aspe

Interview by Erik Bordeleau 161–184

Gobs and Gobs of Metaphor: Larry Bissonette’s Typed Massage

Ralph James Savarese 185–224

Messy Time, Refined

Ronald T Simon

INFLeXions No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience (Nov. 2010)

Transversal Fields of Experience

Christoph Brunner and Troy Rhoades i-viii

ZeNeZ and the Re[a]dShift BOOM!

Sher Doruff 1-32

Body, The Scrivener – The Somagrammical Alphabet Of “Deep”

Kaisa Kurikka and Jukka Sihvonen 33-47

Anarchival Cinemas

Alanna Thain 48-68

Syn-aesthetics – total artwork or difference engine?

Anna Munster 69-94

Icon Icon

Aden Evens 95-117

Edgy Colour: Digital Colour in Experimental Film and Video

Simon Payne 118-140

“Still Life” de Jia Zhangke: Les temps de la rencontre

Erik Bordeleau 141-163

To Dance Life: On Veridiana Zurita’s “Das Partes for Video”

Rick Dolphijn 164-182

Jazz And Emergence (Part One) - From Calculus to Cage, and from Charlie Parker to Ornette Coleman: Complexity and the Aesthetics and Politics of Emergent Form in Jazz

Martin E. Rosenberg 183-277

TANGENTS: No. 4 - Transversal Fields of Experience

3 Poems

Crina Bondre Ardelean

Healing Series*

Brian Knep 278-280

R.U.N.: A Short Statement on the Work*

Paul Gazzola 281-284

Castings: A Conversation*

Deborah Margo, Bianca Scliar Mancini and Janita Wiersma 285-310

Matter, Manner, Idea

Sjoerd van Tuinen 311-336

On Critique

Brian Massumi 337-340

Loco-Motion* (Flash)

Andrew Murphie 341-343 > HTML version

An Emergent Tuning as Molecular Organizational Mode

Heidi Fast 344-359